Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery 2022

The catalogue, Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery, centers the voices of members of the community curators from the Pueblo Pottery Collective. The Pueblo Pottery Collective is a collective of more than 60 Native American community members from twenty-two Pueblo communities in the Southwest. The collective includes potters, designers, and other artists, writers, poets, community leaders, and museum professionals. A small selection of non-Pueblo museum professionals were facilitators and writers for this project and are also part of this collective. The collective was established specifically for the development of the Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery exhibition, to provide insights and perspective on selected works from two major collections of Pueblo pottery: the collection of the Indian Arts Research Center and the Vilcek Collection.

Amplifying Native Voices by Rick Kinsel

This journey, from earliest discussions to the mounting of the exhibition and the publication of the accompanying catalogue, has been a transformative experience—not just for myself, but for the Vilcek Foundation as well. In my twenty-two years with the foundation, first as a member of the board, then as Executive Director and now President, I have sought out unexpected partnerships and collaborations in an effort to expand the bounds of our work and reach as many people as possible with the foundation’s mission: to raise awareness of immigrant contributions in the United States and to foster appreciation of the arts and sciences.

The Vilcek Foundation was established in 2000 by Jan and Marica Vilcek, immigrants from the former Czechoslovakia, and its mission was inspired by their respective careers in biomedical science and art history, as well as by their personal experiences and appreciation for the opportunities o!ered to them as newcomers to the United States. Each year the foundation awards the Vilcek Prizes to immigrants who have made significant and lasting contributions to American society in biomedical research and the arts and humanities. The foundation also awards Creative Promise Prizes to young immigrants who have already demonstrated exceptional achievements in the US. In 2019 we introduced the Vilcek Prize for Excellence, to recognize immigrants who have had a profound impact on both American society and world culture, or individuals who are dedicated champions of immigrant causes. We continue to broaden our reach with external partnerships and new initiatives, including the Vilcek–Gold Award for Humanism in Healthcare.

The Vilcek Art Collection includes more than 400 objects in four major collecting areas: American modernist art, pre-Columbian art, Native American pottery, and art by immigrant artists.The collection continues to grow and evolve from its beginnings as a reflection of the Vilceks’personal taste and interests. The first pieces of Pueblo pottery to enter their collection were a result of time spent in Santa Fe in the early 1990s. The pottery collection has grown under my direction as I sought to expand the Pueblos, time periods, and artistic expressions represented.

I see Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery as an extension of the ideas behind the establishment of the Vilcek Foundation. Both immigrants and Native Americans are underserved communities, and as the foundation uplifts the contributions of immigrants to this country, so we can also use our platform to amplify Native voices. Native American communities have historically been taken advantage of and subject to extensive mistreatment, and we hope to play a small part in the shifting of that narrative. As the original inhabitants of this land, Native Americans have always been here. Although often spoken of in the past tense, they are still here, and, today, sovereignty is a major issue in their homelands. With this exhibition, we seek to extend that autonomy to their art forms by having them decide which pieces to display and how those pieces are spoken about, handled, and interpreted. Native American communities are the best and only resource for Native American art. As we seek ways to decolonize our institutions and practices, we take an important first step by listening to the voices of Native Americans, respecting their knowledge, and supporting their decisions.

A complete rethinking of the Euro-American conception of art and exhibitions is long

overdue, particularly for Native American art, as these are not our stories to tell. From the beginning, I was tremendously enthusiastic about the innovative process and community collaboration conceived by the Indian Arts Research Center in Santa Fe. I respected the boldness of the project and committed to fully supporting it. It is important to me to amplify voices from Native communities and to share our platform and our collection. Sending these pieces back to the Southwest for exhibition, where they can be reunited with family members and ancestors, has transformed and fundamentally changed the collection. Community collaboration has broadened our understanding and appreciation of these pieces, and shown us proper stewardship protocols.

This exhibition and catalogue spotlight an incredibly wide range of pieces, and reveal

that those made by Pueblo people for their own use are just as important as the highly crafted contemporary pieces, particularly those meant for the tourist market. Utility jars, such as the gorgeous Powhogeh storage jar shown on page 274, were made for Pueblo people and kept in their homes. The impressive size and elegant shape of the jar are what initially drew me in, and then the intricately painted designs held my attention. By viewing the spectrum of works in this exhibition, from historical fine pottery to contemporary examples, one can begin to understand how Pueblo people adapted and continue to adapt to the consumer market and consumer taste while still practicing their esteemed tradition of pottery. But I love how this piece represents the Pueblo people and their home life, which ties into family and making food. Pieces like this jar, which clearly shows signs of use, broaden our view of the range and beauty of San Ildefonso pottery.

As a non-Native working with Native art, and as President of a foundation that stewards a collection of Pueblo pottery, it has been imperative for me to learn appropriate terminology, understand public Indigenous knowledge, and ensure a respectful approach. I have been truly fortunate to have had the guidance of several amazing people who were each generous with their time and knowledge. In particular, I am grateful to Brian Vallo, Cultural Advisor (and previously Governor) of Acoma Pueblo, who initiated this partnership in his former role as Director of the Indian Arts Research Center at the School for Advanced Research, and supported it as Governor. Elysia Poon succeeded Brian as IARC Director and fully embraced our partnership, expanding its bounds and managing much of the project, with the incredible assistance of Felicia Garcia (Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians/Samala Chumash) and Monyssha Rose Trujillo (Cochiti, Santa Clara, Laguna, Jicarilla, Diné). Elysia, Felicia, and Monyssha conducted extensive outreach and worked closely with more than sixty Native American community members, from twenty-two Pueblo communities in the Southwest, who gave life to the project. I am immensely thankful to them all for sharing their voices, experiences, and knowledge in the catalogue and exhibition. I also thank Joseph “Woody” Aguilar (San Ildefonso) and Nora Naranjo Morse (Kha’p’o Owingeh/Santa Clara) for their incredible contributions. Woody’s essay perfectly contextualizes our endeavor, from his examination of the history of interest in Pueblo culture to the future of collections stewardship, which relies on the assertion of Indigenous intellect. Nora’s “Clay Stories” weave together beautiful histories, including her own, that illuminate the connections of the Jar Boy Clan and illustrate a deeply held reverence for the earth, for, as Nora notes, “we come from the earth; we are the earth.” I am especially grateful to Erin Monique Grant (Colorado River Indian Tribes) for her invaluable input and assistance with my writings for this catalogue, as well as her inimitable contributions to the foundation’s website—an enormous undertaking that contextualizes and significantly enhances our understanding of the Pueblo pottery pieces.

The Vilcek Foundation could not have accomplished this project without the Indian Arts Research Center and the Native community members. In partnership with the School for Advanced Research, the foundation is thrilled to support community knowledge, voices, and perspectives through Grounded in Clay. We hope that the foregrounding of Native voices and Native knowledge brings additional meaning, not just to individual pieces or to the Vilcek Collection, but to the field in general. There is still so much work to be done, but it is my hope that with this exhibition and catalogue we have created a culturally meaningful framework that other art institutions and museums can implement and build upon for future generations.

San Ildefonso terraced water jar, c. 1860-1920, Ceramic. © The Vilcek Foundation

Acoma jar, c. 1900, Ceramic. © The Vilcek Foundation

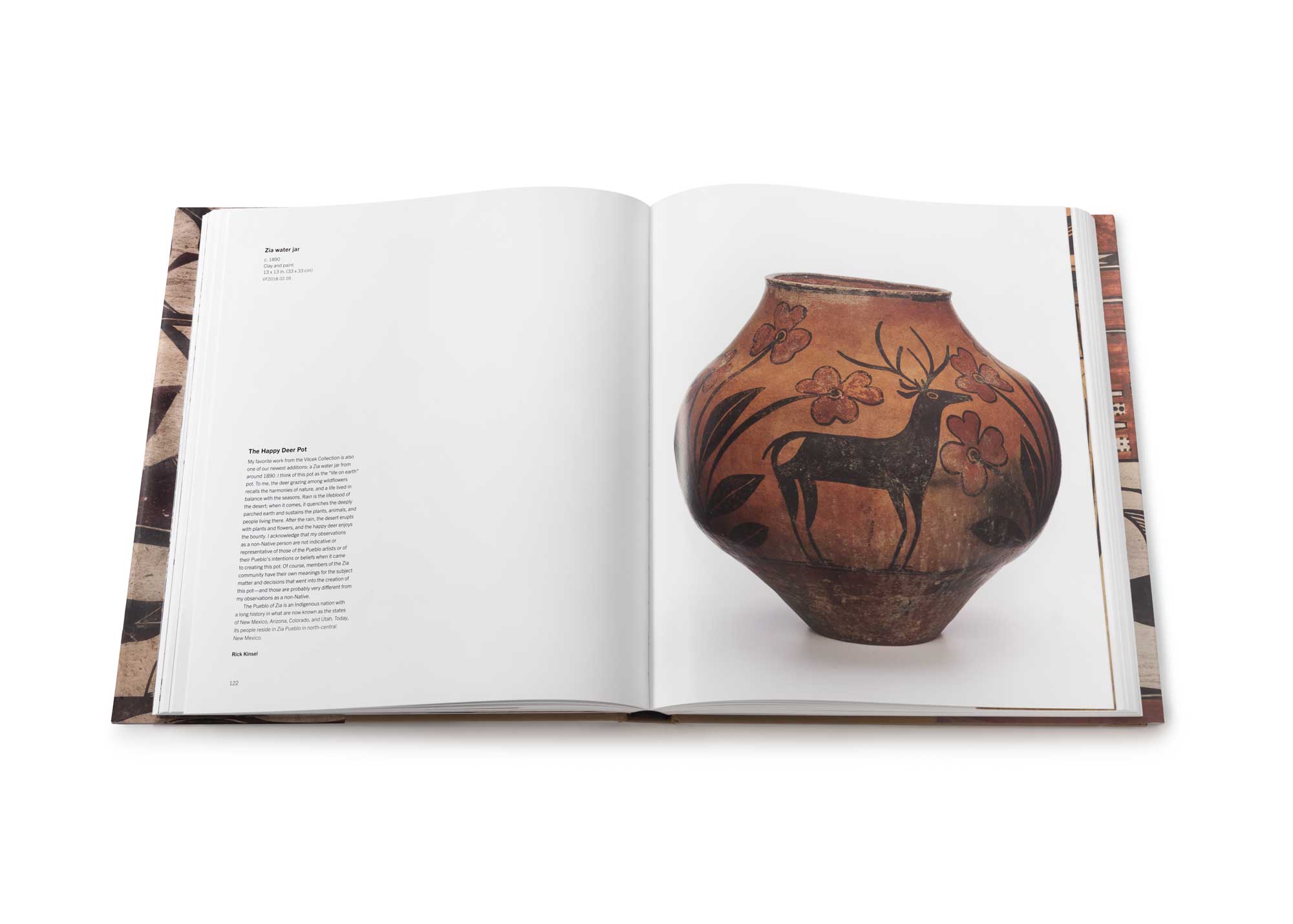

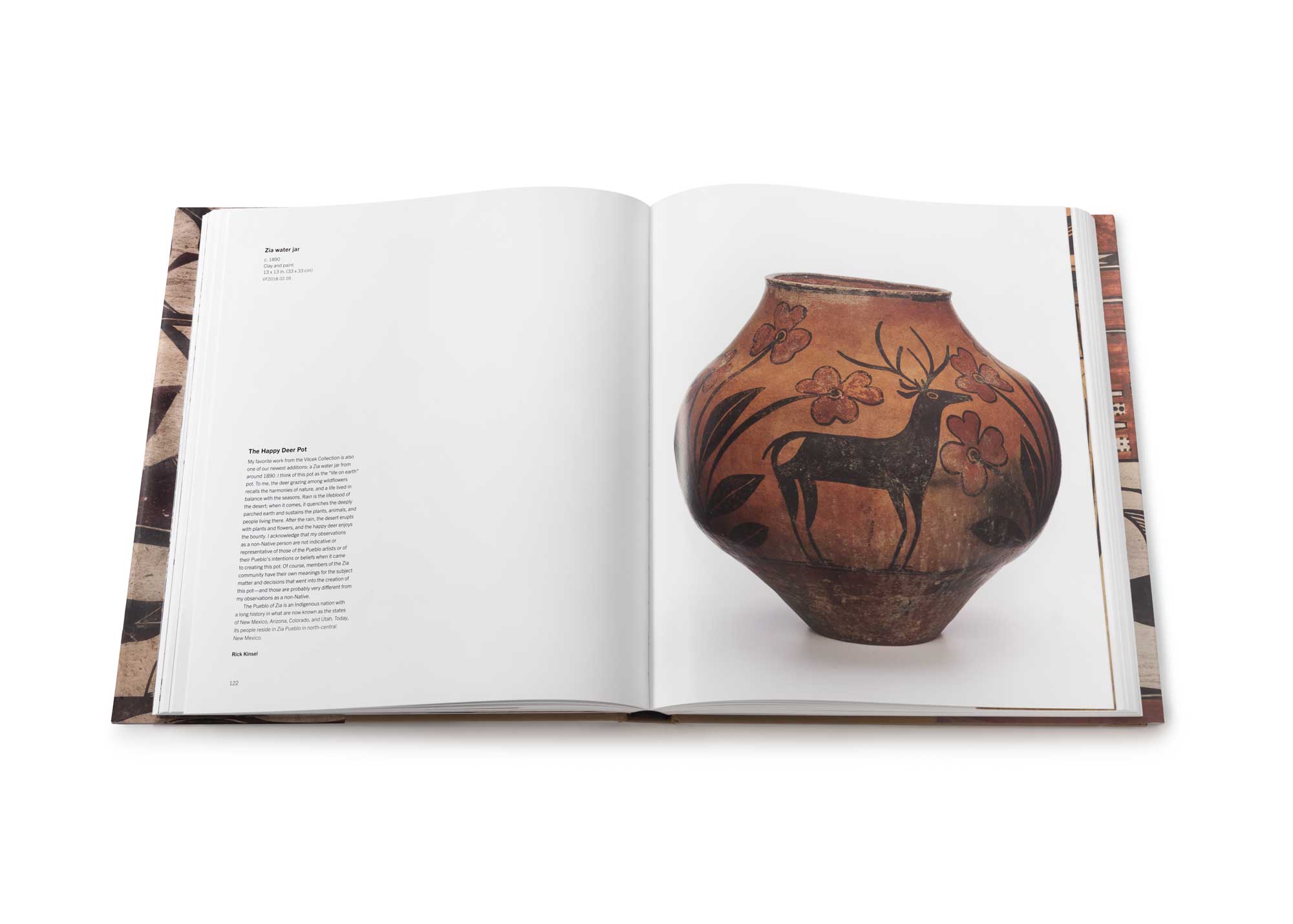

Zia water jar, c. 1890, Ceramic. © The Vilcek Foundation.

Acoma storage jar, c. 1880, Ceramic. © The Vilcek Foundation